Test-Driven Development

Table of contents

In Testing Problems Caused by Generative AI Nondeterminism, we discussed how Generative AI introduces new forms of Nondeterminism into applications that break our traditional reliance on deterministic behavior for reasoning about how the system behaves during design and implementation, including writing tests that are repeatable, comprehensive, and automated.

Highlights:

- When testing a generative AI Component, like a model, you have to write a test using tools designed for evaluating Stochastic processes, such as the tools used for Benchmarks. We build our first example exploring this approach.

- Experiment with the System Prompt and the full Prompt to find the minimally-sufficient content (for reduced overhead) that provides the best results. Prompt design is still something of a black art.

- Map “classes” of similar user prompts to the same response, like answers to FAQs (frequently-asked questions). When it is feasible, this makes those scenarios deterministic (or nearly so), and therefore much easier to design and test. Furthermore, to optimize costs, consider first passing prompts through a low-overhead classifier model. For some classifications, like FAQs, the application can return a pre-formatted response, while for other other classifications, the prompt can be routed to a more powerfully, but more expensive model for inference.

- Think about ways to further process responses to make them even more consistent (like normalizing letter case), while still preserving utility. For example, an application that generates street addresses could be passed through a transformer that converts them to a uniform, post-office approved format.

- Include robust fall-back handling when a good response is not obvious. Spend time on designing for edge cases and graceful recovery.

- For early versions of an application, bias towards conservative handling of common scenarios and falling-back to human intervention for everything else. This lowers the risks associated with unexpected inputs and undesirable results, makes testing easier, and it allows you to build confidence incrementally as you work to improve the breadth and resiliency of the prompt and response handling in the application.

Let us talk about “traditional” testing first, and introduce our first example of how to test an AI component. In our subsequent discussion about architecture and design, we will build on this example.

What We Learned from Test-Driven Development

The pioneers of Test-Driven Development (TDD) several decades ago made it clear that TDD is really a design discipline as much as a testing discipline. When you write a test before you write the code necessary to make the test pass, you are in the frame of mind of specifying the expected Behavior of the new code, expressed in the form of a test. This surfaces good, minimally-sufficient abstraction boundaries organically, both the Component being designed and implemented right now, but also dependencies on other components, and how dependencies should be managed.

We discussed the qualities that make good components in Component Design, such as The Venerable Principles of Coupling and Cohesion. TDD promotes those qualities.

The coupling to dependencies, in particular, led to the insight that you need to Refactor the current code, and maybe even some of the dependencies or their abstraction boundaries, in order to make the code base better able to accept the changes planned. This is a horizontal change; all features remain invariant, with no additions or removals during this process. The existing test suite is the safety net that catches any regressions accidentally introduced by the refactoring.

Hence, the application design also evolves incrementally and iteratively, and it is effectively maintained to be optimal for the current feature set, without premature over-engineering that doesn’t support the current working system. However, refactoring enables the system to evolve as new design requirements emerge in subsequent work.

After refactoring, only then is a new test written for the planned feature change and then the code is implemented to make the test pass (along with all previously-written tests). The iterative nature of TDD encourages you to make minimally-sufficient and incremental changes as you go.

That doesn’t mean you proceed naively or completely ignore longer-term goals. During this process, the software design decisions you make reflect the perspective, intuition, and idioms you have built up through years of experience.

This methodology also leans heavily on the expectation of Deterministic behavior, to ensure repeatability, including the need to handle known sources of nondeterminism, like Concurrency.

Test Scope

Finally, well-designed tests, like units and components themselves, are very specific to a particular scope.

| Test Type | Scope | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Unit tests | Very fine grained: one unit | How does this unit Behave, keeping everything else invariant? |

| Integration tests | The scope of several units and components | How does this combination of units and components behave together? |

| Acceptance tests | The whole application | Does this Scenario for a Use Case work as specified from end to end? |

TDD and Generative AI

So, how can we practice TDD for tests of stochastic components? First, to be clear, we are not discussing the use of generative AI to generate traditional tests for source code. Rather, we are concerned with how to use TDD to test generative AI itself!

First, what aspects of TDD don’t need to change? We should still strive for iterative and incremental development of capabilities, with corresponding, focused tests. What changes is how we write those tests when the component behaves stochastically.

Let’s use a concrete example. Suppose we are building a ChatBot for patients to send messages to a healthcare provider. In some cases, an immediate reply can be generated automatically. In the rest of the cases, a “canned” response will be returned to the user that the provider will have to respond personally as soon as possible. (The complete ChatBot application is described in A Working Example.)

DISCLAIMER:

We will use this healthcare ChatBot example throughout this guide, chosen because it is a worst case design challenge. Needless to say, but we will say it anyway, a ChatBot is notoriously difficult to implement successfully, because of the free-form prompts from users and the many possible responses models can generate. A healthcare ChatBot is even more challenging because of the risk it could provide bad responses that lead to poor patient outcomes, if applied. Hence, this example is only suitable for educational purposes. It is not at all suitable for use in real healthcare applications and it must not be used in such a context. Use it at your own risk.

Let’s suppose the next “feature” we will implement is to respond to a request for a prescription refill. (Let’s assume any necessary refactoring is already done.)

Next we need to write a first Unit Test. A conventional test relying on fixed inputs and fixed corresponding responses won’t work. We don’t want to require a patient to use a very limited and fixed format Prompt. So, let’s write a “unit benchmark”1, an analog of a unit test. This will be a very focused set of Q&A pairs, where the questions should cover as much variation as possible in the ways a patient might request a refill, e.g.,

- “I need my P refilled.”

- “I need my P drug refilled.”

- “I’m out of P. Can I get a refill?”

- “My pharmacy says I don’t have any refills for P. Can you ask them to refill it?”

- …

We are using P as a placeholder for any prescription.

For this first iteration, the answer parts of the Q&A pairs are expected to be this identical and hence deterministic text for all refill requests:2

- “Okay, I have your request for a refill for P. I will check your records and get back to you within the next business day.”

For all other questions that represent other patient requests, we want to return this identical answer.

- “I have received your message, but I can’t answer it right now. I will get back to you within the next business day.”

With these requirements, we have to answer these design questions:

- Can we really expect an LLM to behave this way?

- For those questions and desired answers that have a placeholder P for the drug, how do we handle testing any conceivable drug?

- How do we create these Q&A pairs?

- How do we run this “unit test”?

- How do we validate the resulting answers?

- How do we define “pass/fail” for this test?

Ways that LLMs Make Our Jobs Easier

Let’s explore the first two questions:

- Can we really expect an LLM to behave this way?

- For those questions and desired answers that have a placeholder P for the drug, how do we handle testing any conceivable drug?

It turns out LLMs can handle both concerns easily, even relatively small models. Before LLMs, we would have to think about some sort of language parser for the questions, which finds key values and lets us use them when forming responses. With LLMs, all we will need to do is to specify a good System Prompt that steers the LLM towards the desired behaviors.

Let’s see an example of how this works. First, we will discuss our approach conceptually, the results we observed, and finally explore some insights. Then, we will show you how you can try our example yourself in the Try This Yourself! section below.

First, LLMs have been trained to recognize prompt strings that might contain a system prompt along with the user query. This system prompt is usually a static, application-specific string that provides fixed context to the model. For our experiments with this example, we used two, similar system prompts. Here is the first one:

You are a helpful assistant for medical patients requesting help from their care provider.

Some patients will request prescription refills. Here are some examples, where _P_ would

be replaced by the name of the prescription the user mentions:

- "I need my _P_ refilled."

- "I need my _P_ drug refilled."

- "I'm out of _P_. Can I get a refill?"

- "I need more _P_."

- "My pharmacy says I don't have any refills for _P_. Can you ask them to refill it?"

Whenever you see a request that looks like a prescription refill request, always reply

with the following text, where _P_ is replaced by the name of the prescription:

- Okay, I have your request for a refill for _P_. I will check your records and get back to you within the next business day.

If the request doesn't look like a refill request, reply with this message:

- I have received your message, but I can't answer it right now. I will get back to you within the next business day.

We found that providing examples wasn’t necessary to achieve good results, at least for the two, modestly-sized models we used in our tests (GPT-OSS 20B and Llama 3.2 3B); the following, shorter system prompt worked just as well with rare exceptions:

You are a helpful assistant for medical patients requesting help from their care provider.

Some patients will request prescription refills. Whenever you see a request that looks like

a prescription refill request, always reply with the following text, where _P_ is replaced

by the name of the prescription:

- Okay, I have your request for a refill for _P_. I will check your records and get back to you within the next business day.

If the request doesn't look like a refill request, reply with this message:

- I have received your message, but I can't answer it right now. I will get back to you within the next business day.

TIP:

Providing a few examples is known as Few-Shot Prompting. This technique enables In-Context Learning by providing demonstrations within the prompt that help guide the model to provide better answers. In contrast, providing no examples is known as Zero-Shot Prompting and relies on the model to already be capable of providing satisfactory responses, in combination with any other information in the prompt’s Context. See the website Prompt Engineering Guide for more details.

We tried both system prompts with a number of user prompts (details below) using the following models served locally using Ollama. Links to both the corresponding Hugging Face pages (with model cards and other information) and the corresponding Ollama pages are shown in Table 1:

| Model | # Parameters | Hugging Face | Ollama | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

gpt-oss:20b |

20B | link | link | OpenAI’s recent open weights model. |

llama3.2:3B |

3B | link | link | A small but effective model in the Llama family. |

smollm2:1.7b-instruct-fp16 |

1.7B | link | link | The model family used in Hugging Face’s LLM course, which we will also use to highlight some advanced concepts. The instruct label means the model was tuned for improved instruction following, important for ChatBots and other user-facing applications. |

granite4:latest |

3B | link | link | Another small model tuned for instruction following and tool calling. |

Table 1: The models we used for experimenting.

TIPs:

- These models are available in different sizes. We chose sizes that should work for most developer workstations, but consider smaller or larger versions depending on your hardware resources. Production deployments may require larger versions.

- Ollama provides many models in smaller Quantized forms. Here we use non-quantized models with full 16-bit floating point weights. If you find that the examples are very slow on your machine, try searching for and using one of the quantized versions of each model instead.

- Sample results for all the examples in this site and for some of the models listed above can be found in the repo’s

src/data/examples/ollamadirectory. Results from other models may be added to the repo from time to time. We won’t discuss all of the models listed for all examples, but pick a few to highlight.

With our system prompts and model choices, let’s try some queries.

First, let’s try a set of refill requests:

I need my _P_ refilled.I need my _P_ drug refilled.I'm out of _P_. Can I get a refill?I need more _P_.My pharmacy says I don't have any refills for _P_. Can you ask them to refill it?

Second, let’s try other requests that aren’t related to refills:

My prescription for _P_ upsets my stomach.I have trouble sleeping, ever since I started taking _P_.When is my next appointment?

For all these queries, we executed separate queries where _P_ was replaced with prozac and miracle drug.

For all the models, both drugs, and all refill requests, the expected answer was always returned, Okay, I have your request for a refill for _P_. I will check your records and get back to you within the next business day., with _P_ replaced by the drug name, although sometimes the model would use Prozac, which is arguably more correct, rather than prozac that was used in the “user’s” prompts.

TIP:

To make handling responses more resilient, consider performing some transformations on the generated responses to remove differences that don’t affect the meaning, but provide more uniformity both for verifying test results and for using results downstream in production deployments. For example, make white space consistent and convert numbers, currencies, addresses, etc. to standard formats. For test comparisons when deterministic responses are expected, converting to lower case can eliminate trivial differences.

However, consider when correct case is important, such as proper names, like Prozac. For example, you could use a dictionary of terms common to your domain and make the substitutions before any further downstream processing (including tests).

For the other prompts that were not refill requests, the expected response was always returned by the models used: I have received your message, but I can't answer it right now. I will get back to you within the next business day.

To recap what we have learned so far, we effectively created more or less deterministic outputs for a narrow range of particular inputs! This suggests a design idea we should explore next.

Insight: Handling Frequently-asked Questions

In this app, asking for a prescription refill is a frequently asked question (FAQ). We observed that even small models, with a good system prompt, were able to “map” a range of similar questions to the same answer and even do appropriate substitutions in the text, the prescription in this case.

What other FAQs are there? Analyzing historical messages sent to providers is a good way to find other potential FAQs that might benefit from special handling, such as through the system prompt. When doing that historical analysis, you could use an LLM to find groups of related questions. These groups could be the start of a Q&A pairs data set for testing. For different applications, there may very common prompts sent to a model that can benefit from this special treatment.

This suggests a next step to explore. Should we build a classifier model, whose sole purpose is to return one or more labels for the categories a text falls within, like our refill requests case. (See Evaluation for a more detailed description of classifiers). All messages would be passed through this model first and label(s) returned would determine subsequent processing. These models tend to be small and efficient, because they only need to output known labels, not generated text.

So far in our example, we have the label refill, for the prescription refill FAQ, and the label other, for all other messages.

When a FAQ label is returned, the application can route the message to a low-cost model Tuned specifically for known FAQs, or we perform other special handling that doesn’t use generative AI. So far, we have observed that we don’t even need to tune a special model for FAQ detection and handling.

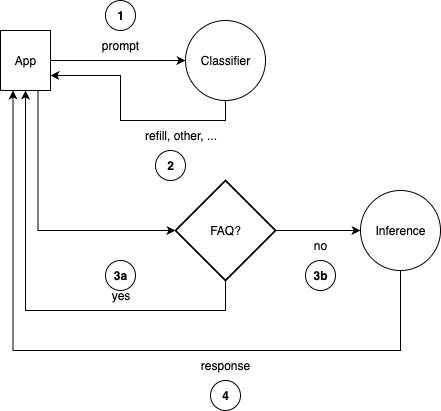

In contrast, the “other” messages could be routed to a smarter (and less cost-effective) model that is better able to handle more diverse prompts. This design is illustrated in the Figure 1:

Figure 1: A simple design combining a classifier and inference model.

The prompt is passed to a “classifier” (steps 1 and 2), which can be a small, general-purpose LLM, like we used above, or a trained classifier. If the label, such as a FAQ, can be processed immediately with a deterministic answer (3a), no further inference is required. Otherwise, the prompt is sent to the inference model for more general handling (3b), returning the response to the app for downstream processing.

Finally, thinking in terms of a classifier suggests that we don’t necessarily want to hard-code in the system prompt the deterministic answers the model should return, like we did above. Instead, we should return just the label and any additional data of interest, like a drug name that is detected. This answer could be formatted in JSONL:

{"question": "...", "label": "refill-request", "drug-name": "miracle drug"}

Then the UI that presents the response to the user could format the actual response we want to show, where the format would be specified in a configuration file, so it is easy to change the response without a code change like the system prompt. This would also make internationalization easier, where a configuration file with German strings is used for a German-speaking audience, for example.

NOTE: For internationalization, we will need to choose an LLM that is properly localized for each target language we intend to support! We will need language-specific tests, too.

Creating and Using Unit Benchmarks

The remaining four questions we posed above are these:

- How do we create these Q&A pairs?

- How do we run this “unit test”?

- How do we validate the resulting answers?

- How do we define “pass/fail” for this test?

In addition, we just discovered that we could have our models return a desired, deterministic response for particular “classes” of prompts, like various ways of asking for prescription refills. This suggests two additional questions for follow up:

- How diverse can the prompts be and still be correctly labeled by the LLM we use for classification?

- If those edge cases aren’t properly handled, what should we do to improve handling?

Several of these questions share the requirement that we need a scalable and efficient way to create lots of high-quality Q&A pairs. One drawback of our experiment above was the way we manually created a few Q&A pairs for testing. The set was not at all comprehensive. Human creation of data doesn’t scale well and it is error prone, as we are bad at exhaustively exploring all possibilities, especially edge cases.

Hence, we need automated techniques for data synthesis to scale up our tasks beyond the ad hoc approach we used above, especially as we add more and more tests. We also need automated techniques for validating the quality of our synthetic test data.

In Unit Benchmarks, we will explore automated data synthesis techniques.

To automatically check the quality of synthetic Q&A test pairs, including how well each answer aligns with its question, we will explore techniques like LLM as a Judge and External Tool Verification.

Finally, Statistical Evaluation will help us decide what “pass/fail” means. We got lucky in our example above; for our hand-written Q&A pairs, we were able to achieve a 100% pass rate, at least most of the time, as long as it was okay to ignore capitalization of some words and some other insignificant differences. This convenient certainty won’t happen very often, especially when we explore edge cases.

Try This Yourself!

Our examples are written as Python tools. They are run using make commands.

Clone the project repo and see the README.md for setup instructions, etc. Much of the work can be done with make. Try make help for details. All of the Python tools have their own --help options, too.

Running the TDD Tool

TIP:

A Working Example summarizes all the features implemented for the healthcare ChatBot example, and how to run the tools in standard development processes, like automated testing frameworks, etc.

After completing the setup steps described in the README.md, run this make command to execute the code used above:

make run-tdd-example-refill-chatbot

This target runs the following command:

time uv run src/scripts/tdd-example-refill-chatbot.py \

--model ollama/gpt-oss:20b \

--service-url http://localhost:11434 \

--template-dir src/prompts/templates \

--data-dir temp/output/ollama/gpt-oss_20b/data \

--log-file temp/output/ollama/gpt-oss_20b/logs/TIMESTAMP/tdd-example-refill-chatbot.log

Where TIMESTAMP is of the form YYYYMMDD-HHMMSS.

Tip: To see this command without actually running it, pass the

-nor--dry-runoption to make.

The time command returns how much system, user, and “wall clock” times were used for execution on MacOS and Linux systems. Note that uv is used to run this tool (discussed in the README) and all other tools we will discuss later. The arguments are used as follows:

| Argument | Purpose |

|---|---|

--model ollama/gpt-oss:20b |

The model to use. |

--service-url http://localhost:11434 |

Only used for ollama; the local URL for the ollama server. |

--template-dir src/prompts/templates |

Where we have prompt templates we use for all the examples. They are llm compatible, too. See the Appendix below. |

--data-dir temp/output/ollama/gpt-oss_20b/data |

Where any generated data files are written. (Not used by all tools.) |

--log-file temp/output/ollama/gpt-oss_20b/logs/TIMESTAMP/tdd-example-refill-chatbot.log |

Where all the interesting output is captured! |

Tips:

- The

README.md’s setup instructions explain how to use different models, e.g.,make MODEL=ollama/llama3.2:3B some_target, instead of the defaultollama/gpt-oss:3.2:3B.- You will need to look at the log files to see how the details of the experimental results.

- If you want to save the output of a run to

src/data/examples/, run the targetmake save-examples. It will create a subdirectory for the model used. Hence, you have to specify the desired model, e.g.,make MODEL=ollama/llama3.2:3B save-examples. We have already saved example outputs forollama/gpt-oss:20bandollama/llama3.2:3B. See also the.outfiles that capture “stdout”.

The script runs two experiments, each with these two templates files:

The only difference is the second file contains embedded examples in the prompt, so in principal the results should be better, but in fact, they are often the same.

NOTE:

These template files are designed for use with the

llmCLI (see the Appendix inREADME.md). In our Python scripts, LiteLLM is used to invoke inference and we extract the content we need from these files and use it to construct the prompts we send through LiteLLM.

This program passes a number of hand-written prompts that are either prescription refill requests or something else, then checks what was returned by the model. You can see example output in the repo:

(Yes, the ollama names for the models mix upper- and lower-case b.)

You may see some reported errors, especially for llama3.2:3B, when an actual response differs from an expected response, but often the wording differences are trivial. Here is one example observed during a test run with an earlier version of the tdd-example-refill-chatbot.py script, where we have taken a log file entry and reformatted it so you can visually compare the actual and expected strings:

Query: My prescription for xanax upsets my stomach. => FAILURE!

Actual response: I have received your message, but I can’t answer it right now...

Expected response: I have received your message, but I can't answer it right now...

Do you see the difference? It’s can’t vs. can't, i.e., different ways of writing a right single quote. Clearly this difference is not likely to be meaningful.

How could we do more robust comparisons that ignore such trivial differences? The tdd-example-refill-chatbot.py script hard-codes a partial solution; it converts both the expected and actual strings to lower case and removes some commonly-observed markdown formatting. In our tests, this eliminated a lot of trivial differences. However, approaches like this are limited, fragile, and quickly grow unwieldy if you try to account for too many kinds of differences.

In addition to these simple modifications, a more resilient approach is a comparison algorithm that helps us decide on close enough. One such algorithm is the Levenshtein distance, which is a measure of the “distance” between two strings.2 This distance is calculated from the minimum number of single-character edits, including insertions, deletions, and substitutions necessary to convert one of the strings to the other string. See the Wikipedia page for the algorithm’s details. The current version of tdd-example-refill-chatbot.py uses this distance calculation.

The Python Levenshtein library is used in the script. Rather than using the distance itself, we use the ratio, defined as follows, where s1 is the first string, s2 is the second string, and distance is the Levenshtein distance between them:

1 - (distance / (len(s1) + len(s2)))

This is number a between 0.0 and 1.0, where 1.0 means the strings are identical. The ratio is convenient for defining a threshold above which we will consider the strings “close enough”. We use 0.95 as the default threshold. A command-line argument can be used to specify a different value. Note that using the Levenshtein distance still doesn’t prove the strings are sufficiently, semantically identical; we are making an assumption here that a low distance (or high ratio) means we can safely ignore small differences.

Also, we still have the limitation that we must define the expected results for every case, which is not a scalable solution. In the LLM as a Judge chapter, we will explore using a second LLM to judge the quality and utility of responses. This is both more resilient and it eliminates the need to manually curate expected responses.

Experiments to Try

In Testing Strategies we will dive deeper into techniques, including “less ad hoc” approaches to unit benchmark creation, evaluation, and use. For now, consider these suggestions for further exploration:

- Try using different models, especially larger, more powerful LLMs. How do the results compare?

- Add one or more additional FAQs. How would you modify the prompts? How would you change how the results are evaluated?

- Experiment with the

systemprompts in the two template files and see how the changes affect the results. For example, when using a small model likellama3.2:3B, does the quality of the generated results improve as you add more and more examples to the template with examples,q-and-a_patient-chatbot-prescriptions-with-examples.yaml, compared to the template without examples,q-and-a_patient-chatbot-prescriptions.yaml? In other words, how can you make a small model work better by careful Prompt Engineering? - How might you modify the example to handle a patient prompt that includes a refill request and other content that requires a response? We have assumed that a prompt with a refill request contains no other content that requires separate handling.

- Try running the script many times and look carefully at the actual vs. expected strings, especially for any cases where the differences are greater than the Levenshtein distance ratio threshold we use (0.95). Are the differences really significant? If not, what could you do in the comparison to automatically treat them as close enough?

What’s Next?

Review the highlights summarized above, then proceed to our section on Testing Strategies, in particular the chapter on Unit Benchmarks. See also Specification-Driven Development in the Advanced Techniques section.

-

We define what we really mean by the term unit benchmark here. See also the glossary definition. ↩

-

There are other, similar distance calculations. See the Levenshtein Wikipedia page and the Python module documentation for more details. ↩ ↩2